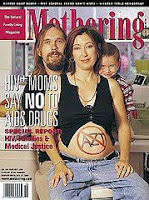

Until the end, Christine Maggiore remained defiant.On national television and in a blistering book, she denounced research showing that HIV causes AIDS. She refused to take medications to treat her own virus. She gave birth to two children and breast fed them, denying any risk to their health. And when her 3-year-old child, Eliza Jane, died of what the coroner determined to be AIDS-related pneumonia, she protested the findings and sued the county.

Until the end, Christine Maggiore remained defiant.On national television and in a blistering book, she denounced research showing that HIV causes AIDS. She refused to take medications to treat her own virus. She gave birth to two children and breast fed them, denying any risk to their health. And when her 3-year-old child, Eliza Jane, died of what the coroner determined to be AIDS-related pneumonia, she protested the findings and sued the county.On Saturday, Maggiore died at her Van Nuys home, leaving a husband, a son and many unanswered questions. She was 52.According to officials at the Los Angeles County coroner's office, she had been treated for pneumonia in the last six months. Because she had recently been under a doctor's care, no autopsy will be performed unless requested by the family, they said.

Her husband, Robin Scovill, could not be reached for comment. Jay Gordon, a pediatrician whom the family consulted when Eliza Jane was sick, said Monday that Maggiore's death was an "unmitigated tragedy."

"In the event that she died of AIDS-related complications, there are medications to prevent this," said Gordon, who disagrees with Maggiore's views and believes HIV causes AIDS. "There are medications that enable people who are HIV-positive to lead healthy, normal, long lives."Diagnosed with HIV in 1992, Maggiore plunged into AIDS volunteer work -- at AIDS Project Los Angeles, L.A. Shanti and Women at Risk. Her background commanded attention.

A well-spoken, middle-class woman, she was soon being asked to speak about the risks of HIV at local schools and health fairs. "At the time," Maggiore told The Times in 2005, "I felt like I was doing a good thing."All that changed in 1994, she said, when she spoke to UC Berkeley biology professor Peter Duesberg, whose well-publicized views on AIDS -- including assertions that its symptoms can be caused by recreational drug use and malnutrition -- place him well outside the scientific mainstream.Intrigued, Maggiore began scouring the literature about the underlying science of HIV. She came to believe that flu shots, pregnancy and common viral infections could lead to a positive test result. She later detailed those claims in her book, "What if Everything You Thought You Knew About AIDS Was Wrong?"

A well-spoken, middle-class woman, she was soon being asked to speak about the risks of HIV at local schools and health fairs. "At the time," Maggiore told The Times in 2005, "I felt like I was doing a good thing."All that changed in 1994, she said, when she spoke to UC Berkeley biology professor Peter Duesberg, whose well-publicized views on AIDS -- including assertions that its symptoms can be caused by recreational drug use and malnutrition -- place him well outside the scientific mainstream.Intrigued, Maggiore began scouring the literature about the underlying science of HIV. She came to believe that flu shots, pregnancy and common viral infections could lead to a positive test result. She later detailed those claims in her book, "What if Everything You Thought You Knew About AIDS Was Wrong?"Maggiore started Alive & Well AIDS Alternatives, a nonprofit that challenges "common assumptions" about AIDS. She also had a regular podcast about the topic.Her supporters expressed shock Monday over her death but were highly skeptical that it was caused by AIDS. And they said it would not stop them from questioning mainstream thinking."Why did she remain basically healthy from 1992 until just before her death?" asked David Crowe, who served with Maggiore for a number of years on the board of the nonprofit Rethinking AIDS. "I think it's certain that people who promote the establishment view of AIDS will declare that she died of AIDS and will attempt to use this to bring people back in line.

Christine Maggiore and the price of skepticism: Questioning theories is usually a healthy pursuit, but in some cases -- such as Christine Maggiore's HIV theories -- the risks outweigh criticisms. LA Times Editorial, January 3, 2009

Christine Maggiore, who was diagnosed with HIV in 1992, waged a long, bitter campaign denouncing the prevailing scientific wisdom on the causes and treatment of AIDS. She fiercely contested the overwhelming consensus that the HIV virus causes AIDS, and that preventive approaches and antiretrovirals can help thwart the disease's spread and prolong the lives of those who suffer from it. Her campaign ended this week with her death at age 52. Her challenge, however, continues, as Maggiore's argument -- that scientific consensus, no matter how established, remains subject to objection -- runs through debates with profound public policy implications. Does smoking cause cancer? Do human activities contribute to climate change?It is admittedly difficult to spot the moment when a scientific theory becomes an accepted fact. It took hundreds of years for the Catholic Church to acknowledge the work of Galileo, and it still flinches at Darwin. Meanwhile, the rest of the sentient universe long ago accepted that the Earth orbits the sun, and all but the most determined creationists see the undeniable evidence of evolution at work. Still, science is a discipline of questions, and rarely is a fact established so firmly th

at it will silence all critics. At the Creation Museum near Cincinnati, the exhibit guides visitors "to the dawn of time" -- just 6,000 years ago. That makes for some startling conclusions, not the least of which is that dinosaurs and humans were created by God on the sixth day and lived side by side. Call it the Flinstones theory.

at it will silence all critics. At the Creation Museum near Cincinnati, the exhibit guides visitors "to the dawn of time" -- just 6,000 years ago. That makes for some startling conclusions, not the least of which is that dinosaurs and humans were created by God on the sixth day and lived side by side. Call it the Flinstones theory.Of course, new questions inevitably emerge from new inquiry and new data. How, then, to judge when a theory becomes fact, when it slips beyond legitimate objection? The test lies in balance: A preponderance of evidence accumulates on one side or the other. Those who contest that evidence must demonstrate the plausibility of alternatives and produce evidence to support them. If the alternatives are implausible, they melt away. Eventually, there is nothing left to uphold the view that the sun is circling the Earth or that natural selection is a secular myth.In some instances, these debates are interesting but not terribly consequential. But sometimes they are of staggering significance. When the theory in question is about the cause of climate change or AIDS, misplaced skepticism, whether cynical or well-intentioned, can lead to grave results.

For years, the South African government joined with Maggiore in denying that HIV is responsible for AIDS and resisting antiretroviral treatment. According to a new analysis by a group of Harvard public health researchers, 330,000 people died as a consequence of the government's denial and 35,000 babies were born with the disease.

Determined to reject scientific wisdom, Maggiore breast-fed her daughter. Eliza Jane died in 2005, at the age of 3. The L.A. County coroner concluded that the cause of death was AIDS-related pneumonia. Maggiore refused to believe it.

No comments:

Post a Comment